Somebody asked recently, why not just have everyone drive electric cars, and make wider roads. They proposed that, for the sake of our freedom and the environment, we should “just get rid of public transit,” suggesting electric cars would be more “green,” and that we would no longer have to wait for buses or walk anywhere anymore.

I would like to dedicate some time here, to imagining what would happen, if we actually went ahead with this proposal.

—

I think we need to wade into this one. So first, we should start with two drawings of the same place.

We will refer back to this place throughout this writing, altering its streetscape by imagining how different modes of transportation might look. In these first two drawings, there is essentially one difference. You will be able to spot that different rather easily.

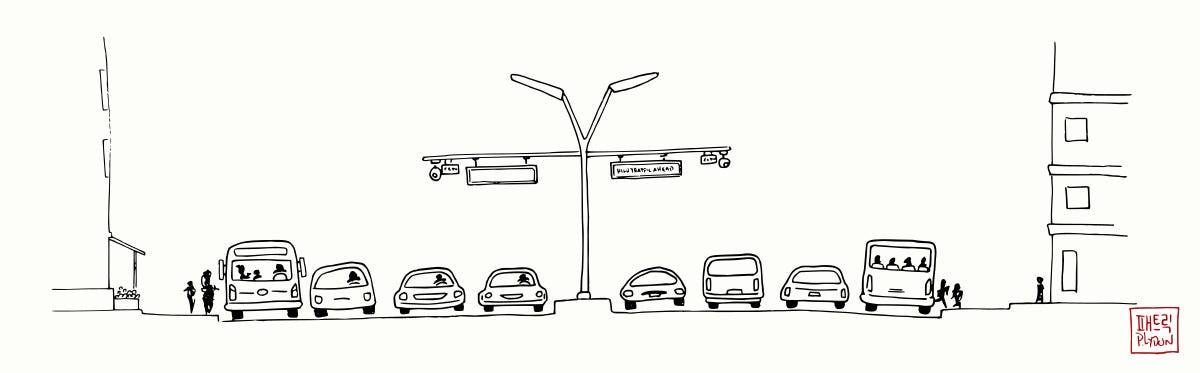

Version one of this place:

Version two of this place:

The difference between the two illustrations is of course, in how people move through or arrive at this place. And from that one difference, many other changes are spurred. In the second version of this place, more people are on the streets. You could also say with reasonable certainty, that the streets would also statistically be safer to cross, that there would be more local business activity, more daily exercise and interaction going on among the people who live there, and thus, more active and healthier residents.

In fact, this is all statistically true about compact urban neighborhoods.

But we are getting ahead of ourselves. Before we can talk about the whole picture and why it works, we should look at the pieces. I want to pull our view then, to just two aspects of this place for now.

How people move through the place.

How the people moving through the place can go about staying in that place for some amount of time.

Moving Through a Place

Let’s take this step by step. Literally. First, looking at just the capacity to move people by walking and cycling.

For step one of this transformation, we transform just four of the eight lanes in the original version of the place. This means we leave two lanes for the rapid bus service. We will also leave two lanes for cars. The rest of the lanes — that is four lanes plus the space that was occupied by the median — will be given to pedestrians, bicycles, and trees.

Here is what this relatively small change might look like, along with some interesting numbers, relating to the approximate people-moving capacities before and after the change.

Putting pedestrians and bicycles in a center parkway with just a single lane of cars to each side, enables us to move about 36,000 people every hour.

If however, that entire space were dedicated to cars, it would move only 9,000 people an hour before turning into gridlock traffic.

Interested in clearing up gridlock in your city? Perhaps remember that removing car lanes can offer better outcomes than adding them. The results are clear in cities that have done this. So long as a network of safe and comfortable cycling pathways is built to serve every area of the city, then a considerable percentage of people will make that switch. If we do it right, both cars and cyclists can have their freedom. Interesting.

As touched on before, a complete network of desirable pathways makes for a more safe, healthy, and environmentally sane way to move around the city. People benefit economically, shops benefit economically, insurance premiums go down. The list of benefits can easily fill a several volume book. Walking and cycling offer better outcomes both for humans and the wider environment on most any indicator or scale you could measure.

I also gather that most would judge a tree-covered pedestrian parkway as being more beautiful and pleasant place to spend time than a gridlocked avenue. Perhaps that is just the tree hugger in me, though?

Going the Distance

Now we take our next step into the water. What happens when we need to traverse an entire city? Is it reasonable to do so on cycling pathways?

In Daejeon, Korea, the city of 1.5 million persons where we are based, I routinely make trips of 20-40 minutes on a dedicated bicycle route along the rivers. Such a ride can take me easily half way across the city.

When a complete network of proper cycling routes are available — Daejeon has some, but not enough to be considered a complete network — I arrive on a bike in similar times to what a car would take on surface roads. An act which I take part in just about daily, in all kinds of weather…

When the safe paths are not there, or if the paths are hopelessly unfriendly to the human psyche — for instance, painted lanes alongside highways or arterial roads with high speed traffic chaos and high noise levels — I choose another transportation method.

Many urban planners and/or politicians worldwide still do not get this point. Our human-powered transit routes could be amazingly beautiful, interesting, ecologically and economically active spaces, but instead of imagining and building such spaces, we too often just drop some paint alongside a highway and call it a bike lane.

However, even if we do have this complete network, it should be said that walking and cycling — especially long distances — obviously do not work for everyone, nor for every urban situation.

So into this scene, we add another tried and true solution.

Adding a metro line to our previous scenario offers a true multi-modal transit corridor, as you might see in many world class cities these days. All of this fits in a smaller footprint than those original six lanes of traffic that we first talked about.1

The metro line allows a further 30,000 people to move through this very same transit corridor every hour. Together with the pedestrian-oriented parkway, this brings us to a capacity over 66,000 people every hour. That is seven times more people compared to the initial car-based street. Enough to empty a stadium after a game gets out without crazy lines or traffic.

Which, coincidentally, is why cities like Yokohama can have stadiums like this, without giant parking lots surrounding them.

Or why the area we previously explored around Juso Station feels and looks like it does.

If you have been to such an urban transit corridor — I feel lucky to have lived adjacent to many, such as the one above in Yokohama — you might also have noticed that this kind of transportation arrangement tends to generate the vibe of a bustling, diverse, alive city.

Are Public Transit and Human-Powered Transit the Answer?

Some might question here, whether public transit, human-powered transit — walking, cycling, wheeling — and human-scaled atmospheres are the only ingredients for a vibrant city. They are not. Of course.

But are they at least essential ingredients?

To answer, we need to take a step back again, to revisit the original question:

What would happen if we completely replaced pedestrian, cycling, and mass transit infrastructure with cars?

Could a bustling city where 70,000 people easily arrive or depart every hour be had by only using cars?

If we tried, what would that look like?

For that illustration, I will need to buy a few new pens. Please hold on.

How about you me back here in two weeks, and we can see what the magical “freedom city” built for cars looks like?

—

Thanks for reading this week. Hope to see you back here next week, for an update on the up-cycle remodeling process at our studio in Daejeon — the previous issue in which we showed the process of making a pretty dandy wood floor from old wood shipping pallets :-)

A standard American vehicle lanes tend to be 3.3 meters wide at minimum; too wide, but that’s another story. A metro train is about 3 meters wide. Add in the platform and other allowances, and six lanes of traffic is enough for a luxuriousy wide metro station.