Welcome! This illustrated essay is part of a new series on Why Urban Japan is So Good. If you are just joining us, it might be a good idea to start with the introduction first. You can also sign up to get this column delivered to your inbox every week.

Free street parking is not exactly free, and in fact most Americans are paying a lot for it without knowing. How exactly does that make sense, and what are the alternatives?

This week we look at the real cost of street parking, and some solutions from urban Japan.

PARKING, BICYCLES, AND ALLEYS

We start this week’s column with an observation that may not seem to have anything to do with street parking. It has to do with my wardrobe. During our years in Osaka, I started to fit into pants that I had not worn since high school. I also felt more fit than I had ever been, and for the first time in my life I looked forward to doing grocery shopping and other errands. I noticed these things, but at first I did not see how they connected with each other — let alone what they had to do with the absence of street parking here.

We lived on an old urban alley and one day I was having coffee in the kitchen, thinking about the day ahead. It looked like a fine spring day and I wondered if Suhee and I might find time to have lunch out and take a break in the park under the cherry blossoms.

As I sipped coffee and planned, a friend rode up on his bike with his daughter in the back seat. He knocked on the kitchen window. Mind you, this kitchen window directly faces the alley, on which the kitchen windows, or living room windows, or shopfront windows of dozens of other homes face.

I opened the window and smiled “Hey, Ben! Hey Emily!” Continuing to sip coffee, we made dinner plans. Emily decided we would have hamburgers. Or maybe it was Ben. However it is, the entire thing happened with both of them still on the bicycle. Then they rode off to the supermarket. My head cocked out the window and I watched the bike glide down the alley and turn out of sight. Ben likes good beer. Mentally, I added a trip to the craft beer shop to my to do list.

This is the moment where an answer came into my head, about why I can fit into my old pants. Making dinner plans, visiting a craft beer shop, taking your daughter to school or the supermarket, having lunch and an afternoon break under a tree. This is a neighborhood where whatever we needed to do could be done locally, on a bicycle or by walking. Though I was still enjoying beer and hamburgers on occasion, I was also — by the sheer design of the neighborhood — walking, cycling, and getting exercise outside every day as I went about errands.

Cars are not allowed to park on the streets here, which is fine. I have not owned a car in over a decade. The homes and streets and shops in this area of the city were built eighty years ago with walking, cycling, and community cohesiveness in mind, and mostly, they have stayed that way. If you have visited the neighborhoods of urban Japan — not necessarily the tourist districts, but the older urban places where people live — you will already know that zero street parking is a real thing here.

To anyone else however, I understand how zero street parking might seem well, just plain crazy.

Here is why it is not.

THE FALSE PROMISE OF ‘FREE’ STREET PARKING

The first thing to note — which should make this all seem a bit less crazy — is that ‘free’ street parking, no matter if it is in America, Europe, or elsewhere, is not free. Every square centimeter of street parking is paid for with your taxes. Every inch of road that needs to be build and constantly maintained, is paid for by you, your neighbors, and the national debt, and the cost is not cheap.

What do cities actually spend on street parking and local street infrastructure?1

Between 5-13% of general government expenditures at the local and state level in the U.S. are spent on roads and public parking, accounting for $206 billion in 2021.

That number continues to go up, and what’s more, $1.7 trillion in federal funding can be attributed just to the construction of highways and roads in the past 12 months.2

At the local and state level, most Americans pay between $500-1,700 in taxes per year for the building and maintaining of local roads and public parking in one way or another. On the federal level, the U.S. spent about $6,800 per adult in the year-to-date on road construction.

Those are big numbers, and it makes sense when we understand that up to 60% of land in some American cities is dedicated to cars and parking.3

In addition to the economic cost, we should note the cost of human life. Deaths due to automotive accidents in the U.S. are up 77% in the past decade, and cars are the number one cause of death worldwide for people between the ages of 5 and 29.4 Chances are that everyone reading this sadly knows someone who has died in a car crash.

WHAT TO DO ABOUT IT?

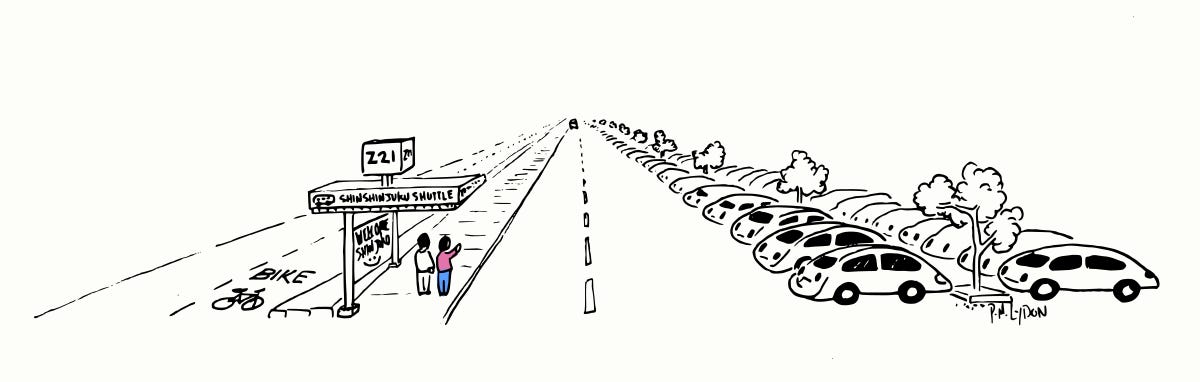

The idea to remove on-street parking and limit urban car use, is not about removing cars altogether — cars and trucks have a use, and in Japan they are often sized right and used in a practical way. It is instead about fully shifting the responsibility for storing a car from the government to the individual. This shift is essentially one of deciding not to subsidize parking at taxpayer expense.

The city described above, decided that alleys and narrow streets without on-street parking are more agreeable than wide streets with parking. Looking at the figures, it is hard to argue with. This shift conserves a huge amount of taxpayer money. If the average American city spends 10% of their budget on roads, the average Japanese city spends around 10% for all civil engineering works combined — roads, rivers, housing, parks, metro, public buildings, and all else.5

These streets are statistically safer, and better yet, all of the money that would have been spent on wider streets and parking, literally goes to things like healthcare, education, local neighborhood parks, and other services instead — programs that some would say are more beneficial to people than a parking spot.

Personally, I can add these benefits to the list: a slimmer waste-line, stronger social relationships with neighbors — because I actually see them face to face every day while walking or biking — and a sense that daily activities done on a bicycle are somehow infused with a certain joy that I never experienced while sitting in traffic or trying to find car parking at the shopping center.

ACTIONS & OUTCOMES

Results will vary of course, but there are pretty clear connections between certain policy actions and outcomes. Narrowing streets. Removing street parking. Building cities that — while still accepting of cars — give priority to being convenient and safe for walking, cycling, and public transit. All of this makes it possible to save everyone money, and to make people happier and healthier while we are at it.

Questions: If your city removed some (or all) of the street parking where you live, what else would need to change for it to actually make sense? Where would you shift that extra tax money, or would you want to see in place of parking?

Next Week: This series continues with another deep dive into the urban Japanese neighborhood.

Read Another Story: My neighbor Ben appears in another story from 2 years ago, comparing the design and social outcomes of alleys and car-based streets. You can read it here:

—

Thanks again, for letting me into your world this week. You can help this project grow by 1) thinking of a friend or colleague who might like this work, and 2) sharing it with them:

If you are not signed up yet to get these stories to your inbox, you can go ahead and do it below. You can also join our supremely kind club of paid subscribers:

https://www.urban.org/policy-centers/cross-center-initiatives/state-and-local-finance-initiative/state-and-local-backgrounders/highway-and-road-expenditures

Sum of spending in 12 months as of July 2024, the latest figures available at the time of publication. From the U.S. Census Bureau, Total Construction Spending Highway and Street in the United States [TLHWYCONS], retrieved from FRED:

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=1uxxx

Depending on your city, anywhere from 1-49% of urban space is dedicated to off-street parking alone, and 18-30% of urban land overall is dedicated to streets and street parking. In total, some cities dedicate upwards of 60% of land in central business districts to streets and parking.

https://thehill.com/changing-america/resilience/smart-cities/4162455-paved-paradise-maps-show-how-much-of-us-cities-are-parking-lots/

https://urban-mobility-observatory.transport.ec.europa.eu/news-events/news/identifying-amount-urban-space-occupied-roads-2021-06-21_en

https://oldurbanist.blogspot.com/2011/12/we-are-25-looking-at-street-area.html

According to the WHO report: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/road-traffic-injuries

https://www.soumu.go.jp/iken/zaisei/r05data/chihouzaisei_2023_en.pdf

Very astute observations and hardheaded stats combine very effectively here. I like how you always mix the personal and the public, because of course they are intimately connected.

Thanks for the article, as always, it's great! Looking at your drawings, I couldn’t help but wish to live in a town like this.

Oh yeah, I wish street parking was removed in my area. I live in a suburb where there is virtually no public transportation other than the occasional bus.

Because of this, in my area, many people own cars and almost all public spaces are filled with cars.

In my opinion, it is very important to develop public transport in such areas. I can see that a light tram would fit perfectly into the landscape of my suburb, taking people to work in the morning and bringing them home in the evening. And for moving around the suburb, a bicycle would be ideal, so I would like to see more bike paths and bike parking near shops and restaurants.