During a few short days in Ukiha, I walk a lot. I always walk a lot. Even on days like today, when it is 34-degrees Celsius (93F) and 95-percent humidity, and my entire body is drenched in sweat. I walk diligently — so long as there is enough water going into my system. Water, I notice, is a theme here in Ukiha. As much as one tries to meander away from it, something always pulls you back to the canals that flow through this town.

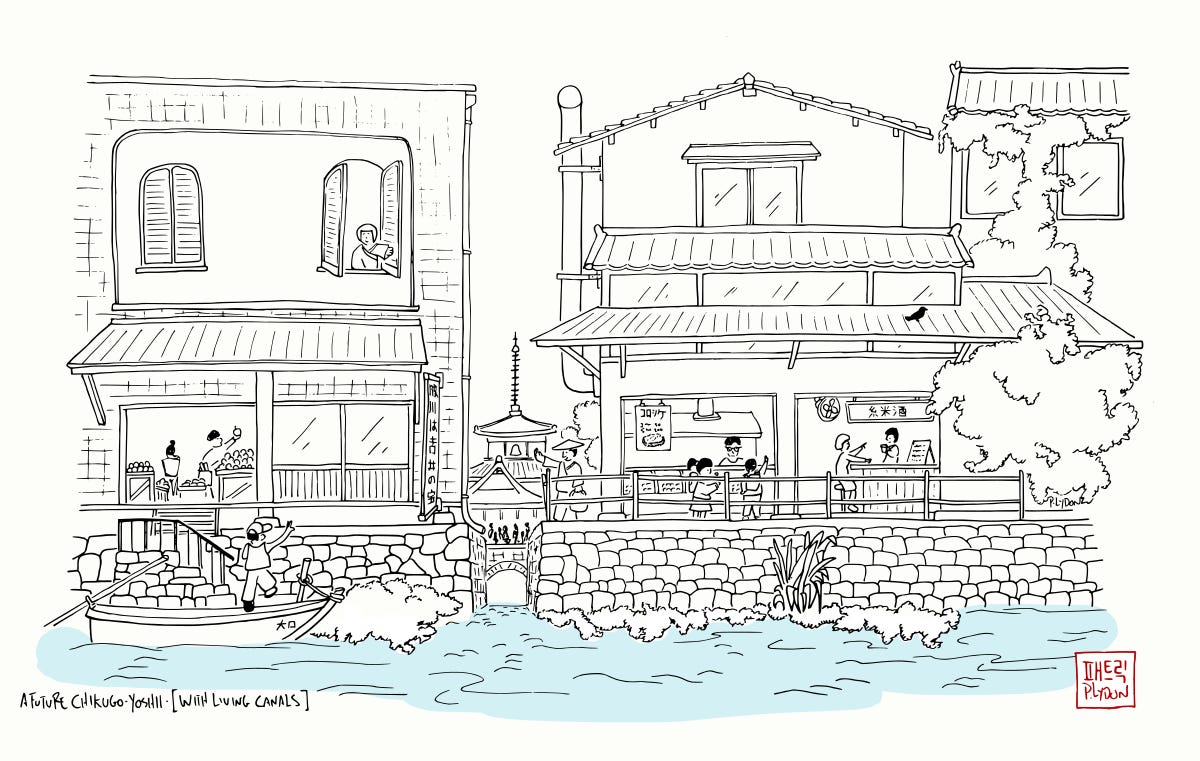

Perhaps that is just because there are so many of them. If it were not for the absence of gondolas, one might mistake here for a Japanese Venice. But gondolas or not, the canals themselves actually provide plenty of reasons to stroll alongside them.

There is a good deal of science out there that tells us living near water — whether canal or ocean — is beneficial not only for our mental condition, but for our physical condition as we age. While these studies offer plenty of health-related reasons why water should be a feature of every neighborhood, the canal system in Ukiha came about for a different reason. It was built for the farmers. A local man sitting at the pub which fronts the guesthouse tells me that Ukiha’s existence is tied to the canal — without its water they would not be able to grow rice in the traditional manner.

The same man asks me what I think is special about Ukiha. My answer is of course, the canals. He smiles, acknowledging that these days, the positive effect of the water moving through this town goes far beyond the utility of growing rice.

As the main canal enters the city, the water bends around corners and is divided into smaller channels. Working its way in between nearly every block, sometimes this diverted river water flows wide and deep, and other times it trickles through narrow passages alongside walkways that only a cat would be comfortable to pass along.

Regardless of how wide or narrow a water channel might be though, you can always feel its presence. A large number of homes and shops here have direct access to this water, by steps from a back door or kitchen, or even via small docks.

In the wealthiest of homes — some of them now open permanently to the public — this water is diverted into backyard gardens, where it creates miniature waterfalls, and streams that meander 24/7 alongside moss-covered stones and hydrangeas just outside the engawa.

These canals make a difference in temperature, too. My nights in Ukiha were the first time in a week that I could take a night walk without sweating. On the second night in particular, a cool breeze swept along the main canal. A pigeon swooped over my head, dove down near the water, and then flapped its way up to perch on the roof of an old house. The pigeon’s talons made clanks and pangs and scratches as it navigated the warped tin roof.

I stood under a Willow, just across the canal from the pigeon. The bird stared at me. He bobbed his head, looking down at the canal for a moment, then back up at me. He panged and clanked some more, clumsily slipping his way across the roof, and then performed the same look, down at the water, up at me. Maybe this pigeon was just hoping for bread. Or maybe it was trying some weird mating dance out on me. Whatever it was, in that moment it felt like we were both connected to the water in some way.

Why was it so attractive?

I left Ukiha the next day, and yet the canals and the old house on which the pigeon perched stayed in my mind. I had been to the old mansions in this town, and by that measure, the tin-roofed pigeon house was not so remarkable. It was abandoned, had no garden, and parts of it were likely soon in danger of falling into the canal. This is how it was. But I try not to dwell on how something is, for I had also seen here in Ukiha, old buildings greatly revitalized through the creativity and determination of a young generation.

And so, dilapidated as this old pigeon house by the canal was, I saw the same kind of possibility. I saw what it could be, if just given a bit of love.

You know, every place has the possibility to become beautiful and alive if just someone — one person, two people, a small group of people, a pigeon — sees the inherent value in that place and its features. This value may bring fortune. A fortune that belies the dollar signs. A fortune that is about putting your love, energy, and individual spirit into something that you think is true and good. The return on investment from such acts is always beyond valuation.

Around the canals, where foreigners and locals meet in small guesthouse pubs, where shops offer all sorts of delicious local goods, and where people sit peacefully to take in the water trickling through backyard gardens, this seems to be how much of Ukiha and the area around Chikugo-Yoshii comes about these days.

Canal or not, realizing and nurturing the value of where you are is also in principle, how these kinds of neighborhoods will come about where you live and work, too.

There are more than 250 of you here now, and we are slowly but constantly growing. Thanks for coming along, and for continuing to share this work with others. If you really enjoy what I am doing here, why not join our group of paid subscribers? They are the patrons that keep this ship moving down the canal.

However you do it, thanks for being here to explore The Possible City with me.

This story is a continuation of a series on my trip to Kyushu, Japan. If you missed any of the previous stories, it starts here:

Reasonable Urbanism: A Ferry to Japan

Yesterday the winds were wailing, and the waves rolled me off my futon at least once during the night. Overall though, the experience was rather breathtaking in a good way. I had said I might need to visit Japan for this series. It is not so far, really. Yesterday I caught a train to Busan, and a few hours later, boarded the

I love this story. I agree that living next to water nourishes the invisible aspects of our selves. I was so happy living on a houseboat docked at Gate Five, Sausalito, in 1968. Likewise, on the mesa overlooking the ocean in Bolinas. Or childhood summers spent at the beach house my grandmother would rent where Topanga Creek met the Pacific Ocean.

I loved walking and taking trains with you and Suhi. Sending so much love! <3