This illustrated essay is part of a series on Why Urban Japan is So Good, and if so, why does it matter to the rest of the world? If you are just joining us, you might want to start with the introduction first. You can subscribe to these also, if you’d like to get this column regularly.

—

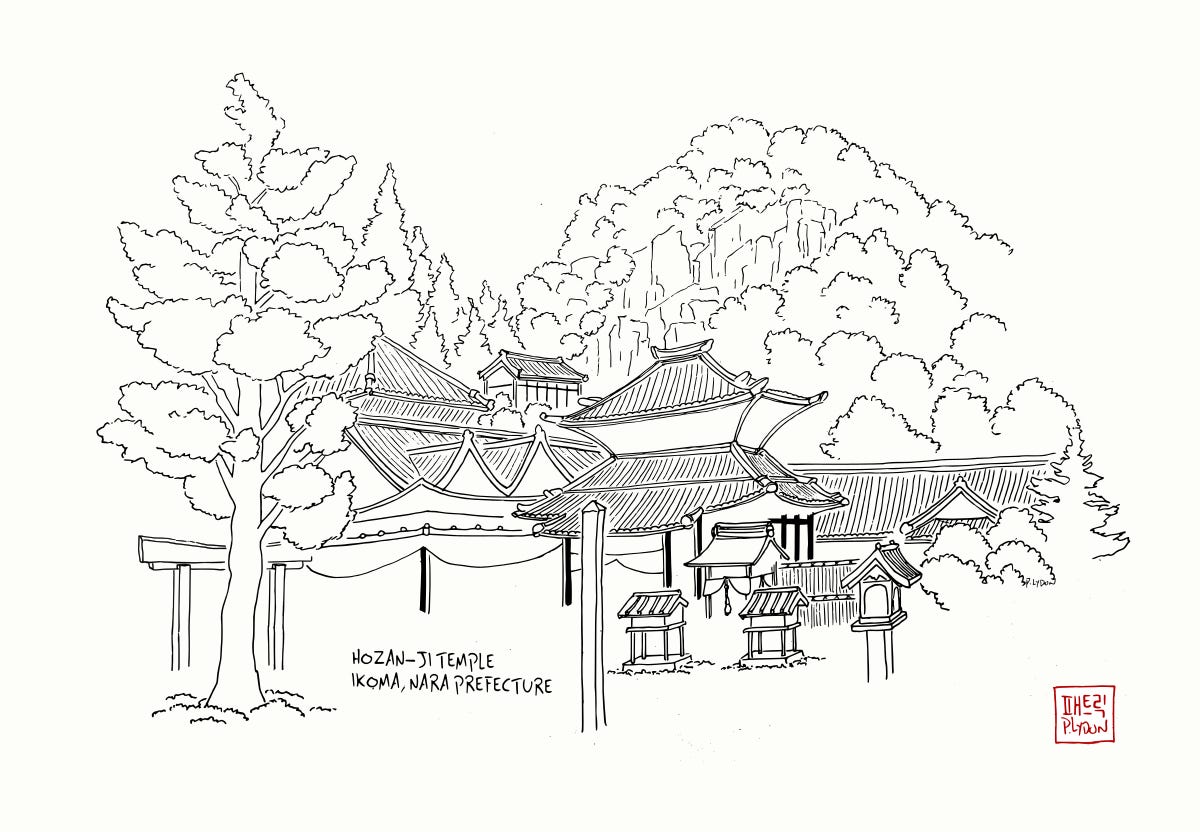

The cable car station where I got off last night is named for Hozan-ji, the 17th-century Buddhist temple with buildings and staircases sprawled throughout the narrow forested valley here. But monks have been here for longer than the temple — some say this valley has been recognized as a particularly spiritual place for wisdom seekers the past thousand years or more.

This morning however, I am just here for a walk. Moving through the shadowy cedar forest, the komorebi flickers here and there — sun filtering through layers of trees to light up the roof of a Shinto shrine, incense smoke wafting, a Jizo statue. The walk reveals not just one, but various different temples, Japanese Shinto shrines, yoga retreats, and the other institutions that typically exist around old sacred places in Japan.

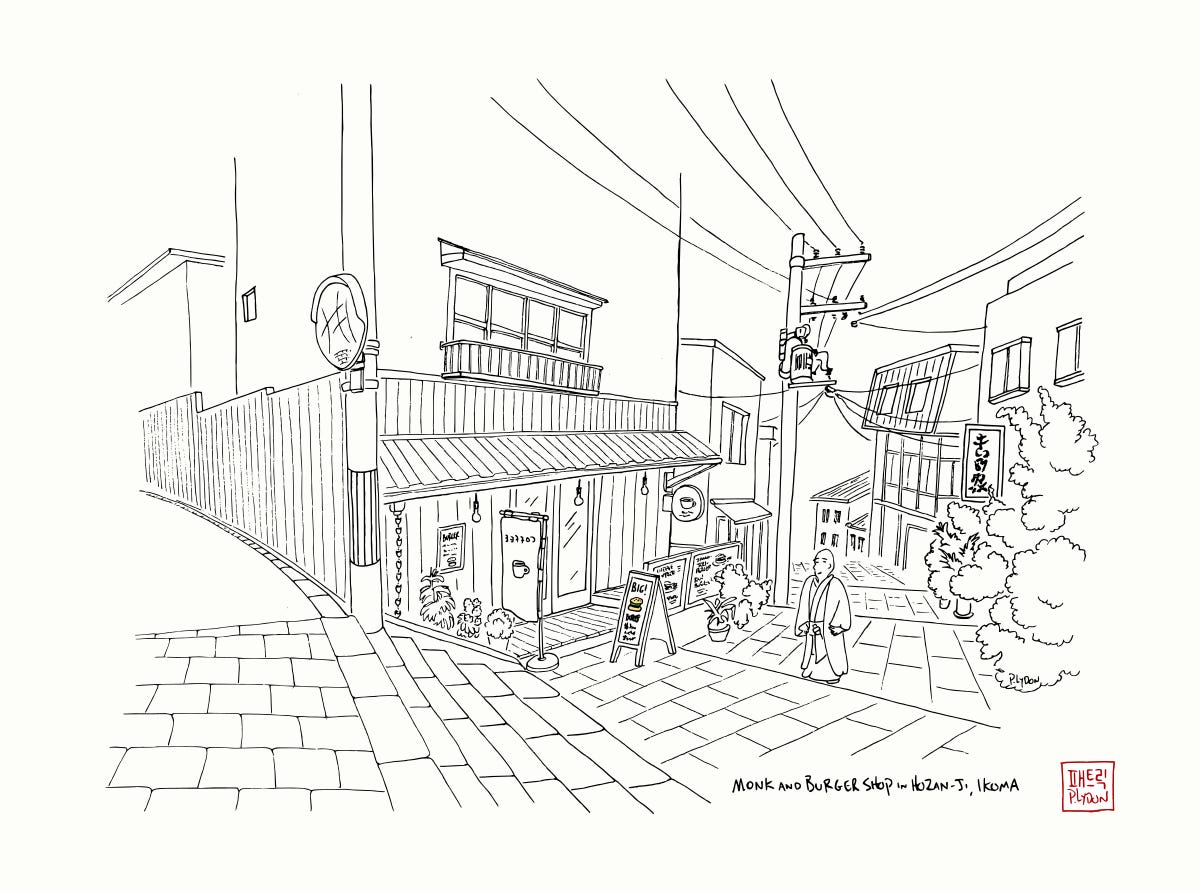

Yet walking the path up to the temple, I also find there is a burger restaurant, a Christian bible study institute, and a mountain-top theme park with roller coasters. These strange contradictions not only share the same wee corner of this sacred mountain, they are purposefully connected to each other by a cable car, running every 20 minutes from just outside Ikoma Station.

This all reminds me of a specialty of Japan: piecing together different ways of seeing, in some strange kind of relative harmony.

The other day a friend in Kyoto mentioned that around the end of each calendar year, Japanese people celebrate the birthday of Jesus. Then, they visit a Buddhist temple. Then, make their way to a local Shinto shrine. The depth of engagement in these acts is debatable — Christmas for instance is typically celebrated with birthday cake and KFC. But the point stands, that an individual person in Japan will commonly encounter and accept the presence of Christianity, Buddhism, Paganism, Animism, and Colonel Sanders, all without any thought of there being major conflict between these ways of seeing and being.

Insoluble conflict, they say, does not exist in the world of nature and the divine, it is purely a product of the divisions we create — judging and fearful minds, closed off to different ways of seeing, tend to lead us into conflict.

After an enjoyable walk through the sacred and profane of this valley, I circle back and decide to stop at the burger shop. Strange enough, they have a nice looking scone and coffee set. In a quaint room where two other customers sit and quietly chat across the way, I work on finishing an illustration of a valley with stone figures and a waterfall — you’ll see it below. But I come up against a barrier in the process. One of the stones in the scene has Kanji characters carved into it, and my Japanese language is far too limited to make out the meaning of the characters. I decide to ask the shop owner, a very kind man from Malaysia. He is not sure either — but he has an idea. Without a moment of hesitation, this man whisks me over to the table where the two other customers sit.

When we approach, the two women are startled. Taking note of their confused looks, I then watch as the owner puts my drawing on the table and explains to these middle-aged ladies that I need help with Kanji. He then smiles and ducks back into the kitchen, leaving us alone. Timidly, I explain what I am doing. They in turn, look at the drawing, then at each other.

Suddenly their expressions both light up with eagerness. Relief comes over me as notepads and phones are pulled out and they dive into the problem of the Kanji with all of their energy.

Over the next half hour the three of us sit together, chat, think, and laugh a lot. I learn they are both moms and childhood friends. Eventually we also solve the problem of the Kanji written on the stone. One of the characters is ancient, and not commonly used these days — all the more fun to decipher.

Together, we surmise that the writing means “Boulder Valley Waterfall,” or something of that nature.

Of course!

You might also notice in the drawing, that there are four figures standing behind the stone. These figures have swords and are definitely not the common smiling Buddhas we might be used to seeing. It felt a bit eerie to encounter these fierce looking figures at first. I later find out that they are related to the Buddhist Wisdom Kings, and that their swords are apparently used not for attacking per-say, but for slicing through the shadow of ignorance, and thus removing obstacles to wisdom and enlightenment. A somewhat foreign concept, but I suppose it makes sense.

Back at the cafe table, the three of us celebrate our “stone deciphering” achievement with high fives and selfies. The level of joy at the table might be a bit ridiculous, but I love it. It is a pure joy that feels well placed, even if our kanji researching achievement was seemingly small. Our work might not have been a triumph of ultimate wisdom, but through maintaining open minds, we did appreciably slice through ignorance, remove a few borders, and gain something of an enlightening experience, both about the Kanji, and about each other.

Later that night these two moms would treat me to dinner. I met one of their kids, and was gifted a bag filled with souvenirs for me and Suhee. By the time we parted ways, we were embracing each other like old friends. I have little idea the ways in which such kindness manifests in this world, but I do have a sense that we need more of it.

As it is, moments like this bring me to tears. And thought I can not point out exactly where these tears come from, I guess it is just as much from happiness, as it is from wondering why we humans can’t be like this more often.

Thinking back to that valley in Ikoma, where Buddhist temples mingle with Christian bible studies, roller coasters, and burger joints, I think about those stone Wisdom Kings. Perhaps they did work their magic on that place, slicing through ignorance and opening minds. Or maybe, just maybe, that kind of wisdom is always hanging about, just waiting for us to engage it.

Well, ’tis the season.

—

Thank you to Akiko and Hiroko, the two kind ladies who helped me figure out the Kanji on that stone. After that, my father-in-law Juseok helped too, kindly painting the Kanji in calligraphy, which I then placed on the stone. Team effort.

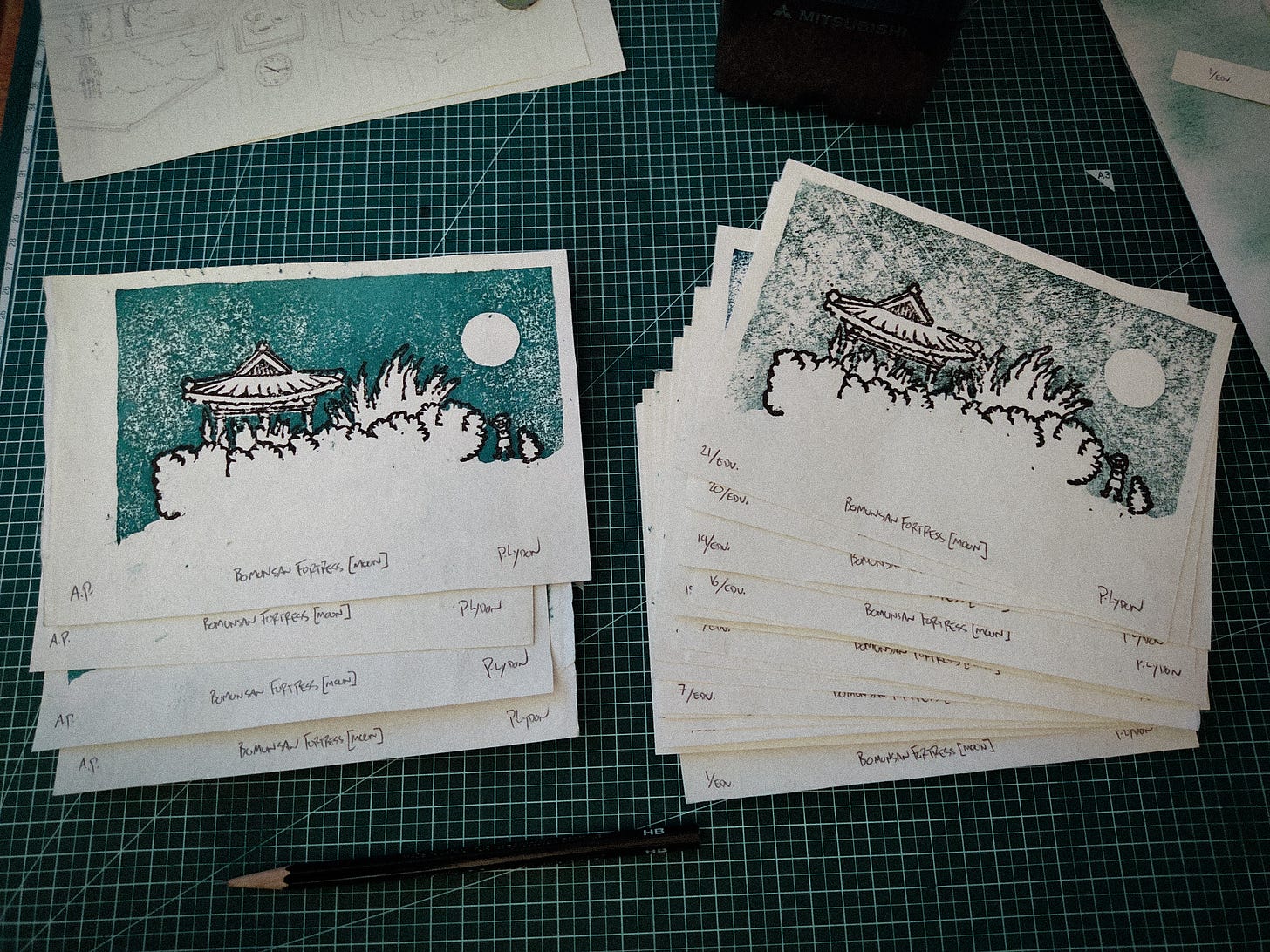

On another note: Paid subscribers of The Possible City are getting an art gift from me in the form of a wood block print.* The print depicts Bomunsan, my favorite urban mountain here in Daejeon. I made this print fully by hand right here in the studio, and the first print run is exclusively for paid supporters of The Possible City.

There are still 7 prints remaining. If you want one, sign up as a founding member or yearly paid subscriber before the end of the year. If we get more than 7 people doing this, I will do another print run when I am back in the studio in the new year. Hey, a guy can dream.

*This offer is for founding members, yearly paid subscribers, or monthly paid subscribers who have been supporting The Possible City for a year.

—

Questions: What ‘ignorance’ do you want to slice through this coming year?

Next Time: An update about some big plans we are making for the coming year.

Read Another Story: This is one of the first stories from The Possible City, written now just over 3 years ago. In it, an old paper maker teaches us about beauty, money, and why we have such a hard time finding a value that speaks to both.

SHORT #3: How to Make it Beautiful (Part I)

—

Thanks again to all of you, for letting me into your world this week. You can help this project grow by taking a moment to think of someone else who might like this work, and then clicking the magic button below.

If you are not signed up yet to get these stories to your inbox, do it below. You can also join our supremely awesome club of paid subscribers.

I'm struck by the similarity of the mingling of cultures on the mountaintop in this essay and the description of how the paper-maker in the linked story uses various old and modern technologies in his craft. It"s a recognition that these seemingly contradictory things exist, and can exist alongside each other, without tension, if acknowledged as coming from the same human impulse.

I want to slice through the ignorance that being stingy with our love is an effective strategy. All around me are folk afraid to be the courageous initiator of sharing love….afraid to compliment…afraid to hug…afraid to say I love you…afraid to be on the receiving end of rejection after sharing this love! I am sharpening my blades…