Welcome back! This illustrated essay is part of a series on Why Urban Japan is So Good. Is it really? If you are just joining us, it might be a good idea to start with the introduction first. You can also sign up to get this column delivered to your inbox every week.

—

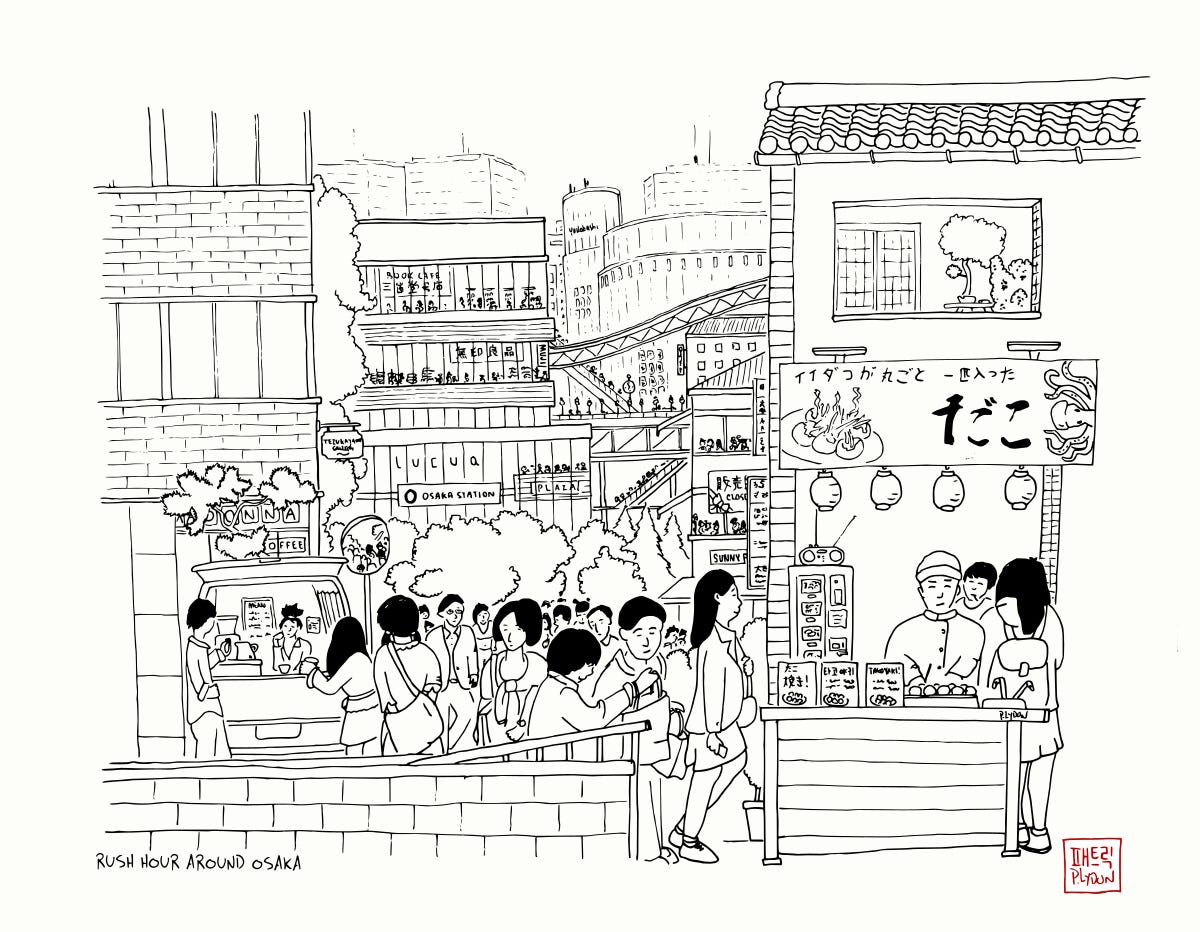

This week, we explore how smallness and awareness join forces, to help make the particular brand of urbanism in Japan work as it does. How does it feel to be in a place? I hope you can linger with the text and illustration this week a bit, when you get to that point in the writing.

A FLOWING MASS OF PEOPLE

On an autumn morning in this urban neighborhood, the sun is out and scarves are fluttering on the wind. A constant flow of cyclists and pedestrians make their way here and there, somehow managing to move up, down, side to side, and every other which way along a wide sidewalk. As a fresh Westerner here many years ago, I was both mesmerized and baffled by this flow of people.

Baffled because the bikes and people mostly ignored the markings on the paths that told people where they should be. An arrow points one way, and bicycles ride the other way. In the underground too, there were unwritten rules for where one should stand on an escalator, they changed from one city to the next, and when multiple passages of people intersected, well, it seemed like the only rule was chaos.

And somehow, it works.

AWARENESS IN THE CITY

In time something becomes clear, about the chaos this fresh-eyed Westerner first saw in the streets and subways and train stations. In time you realize that the chaos was never really there to begin with. It was only in your mind. You knew the rules of walking and cycling based on where you grew up, and things don’t work like that here.

If we view the world around us through personal judgment, chaos looks dissonant. If we view the world around us through awareness, chaos becomes far more peaceful. There is a theory about this somewhere, isn’t there? However it is, awareness must be a big part of what makes the mega cities of Japan possible. Walking here on a street in Osaka, or through the Shibuya crossing in Tokyo, or the maze of train station corridors in any major city in Japan, the movement of people comes across as an extremely successful mass-effort at awareness.

One does not get through a multi-intersection-underground-subway-station-shopping-mall-maze of ramps and pedestrian corridors in Japan by rules and stop lights. They get through by keeping watch of others and making slight adjustments as they move, accepting minor inconveniences or shifts in one’s trajectory or speed, in order to keep the flow moving for everyone.

This is akin to a natural flow of intersecting rivers. And yet that flow is also masterfully divided and controlled in its own way, not by signage and metering lights, but by the very makeup of the city itself.

Take a breath and linger with me in this for a bit.

THE GRAND FLOW OF SMALL THINGS

In a mature city, not everyone does the same things at the same time. While there may be a rush hour, the phenomenon expands in space and time in the mature city. In Tokyo, for instance the rush hour population includes around 15 million daily commuters — for reference, that is about 90x the volume of a Silicon Valley rush hour. Yet even with all those people, if you are walking and taking public transit in a commute in urban Japan, the experience is not stop and go traffic, but a flow, through a layered series of interconnected alleys, paths, corridors, and trains — though admittedly, you might rub elbows a bit more.

A WATERFALL VERSUS A SERIES OF STREAMS

Here again, we come to smallness.

Perhaps you think that Osaka or Tokyo or Nagoya are big? They are wide, sure. But when you are inside one of these cities for long enough, you come to realize how smallness might actually be more important than the big. For sure, smallness and granularity play a critical role in the formation the particular atmosphere of these mega cities.

Imagine with me for a minute, that people in our urban Japan commute are individual molecules of water — as Genzaburo Yoshino once wrote.

If we have a sloped hillside where all of that water needs to get from the top, down to the valley below, one way to do this is with wide and deep channel with waterfalls. This will funnel a lot of water tumultuously through a place all at once. It works, but if you are a water molecule, it’s one heck of a ride, and also difficult to get off of at any point.

Yet what if we instead moved that water from the top of the hill to the valley by way of many small channels, a series of holding pools and smaller waterfalls. This allows us to potentially move more water, yet at a slower pace, more calmly. The water not only has a diversity of different ways to go, but also has places to linger a bit. This series of small, interconnected places to flow and linger, is a big part of the Japanese city. The small streams are alleys and corridors. The holding ponds are restaurants, izakayas, shops, and whatever else pulls people aside momentarily. Some people even percolate into those places and decide to stay.

Smallness. Awareness. Smallness makes local train stations surrounded by diverse walkable neighborhoods possible. Awareness ensures that everyone can move through all of it smoothly.

Here, in this flow of people, walking quietly with a co-worker through alleys filled with dumpling steam and charcoal grills, meandering into a pub, sitting under a Ginkgo tree in the park, one forgets how this all works. At the end of it all, I’ll take the Yotsubashi line, you’ll take the Sennichimae line, and we’ll do it again tomorrow.

Is that how this dance should go?

Perhaps that is how it should go.

—

Questions: Is that how this dance should go?

Next Week: I need a little breather. We are opening our studio space in Daejeon this weekend. Wish us well! I’ll send an update about the space next week, if there is interest? Then, we return to urban Japan in two weeks.

Read Another Story: In writing the closing this week, I was reminded of this story, which shraes the theme of how we nagivate life with awareness.

—

Thanks again, for letting me into your world this week. You can help this project grow by taking a moment to think of someone else who might like this work, and then clicking the magic button below.

If you are not signed up yet to get these stories to your inbox, do it below. You can also join our supremely awesome club of paid subscribers.

Yes, it's the little details, the granularity, the connections seen and unseen, that make urban Japan what it is. I see this all the time, and it's what I try to document, perhaps subconsciously so, in my photographs. If you're interested in what I do, have a look at my page on Flickr: https://www.flickr.com/photos/gregapan/

The opening paragraph about pedestrian flow reminds me of a chapter in Alexandra Horowitz’s book called On Looking. Humans will naturally fall into a flow in crowds (only recently disrupted by people engaged head down on phones). I think it’s a book you might enjoy if you haven’t come across it yet. In it, she takes city walks with different types of people - a biologist, a type face designer, a child, her dog, a blind person.. its fascinating to read how each one navigates the city differently and what they see as they do.