Hi friends. This week I want to depart a bit from the usual and share the story behind a recent artwork — and the surprising path it took to make it. It involves a forgotten printing method, a pile of golden poop, and a different way of seeing beauty.

—

I haven’t shown new artwork in a gallery since the Seoul Biennale in 2023. But when a sculpture artist in Sakai introduced me to a lost printing method, it sparked a new opportunity.

It started last year, when good friend Yukino took me on a studio visit to meet sculpture artist Yoshio Hashimoto.

This visit opened my eyes in a lot of ways. Firstly, to see and be inspired by how active Yoshio is in promoting the arts as a way of seeing the world, and sharing his wealth of skill and understanding with people around him.

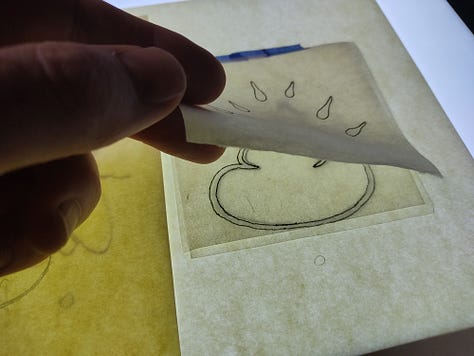

Secondly, he introduced me to an old process, invented by Thomas Edison. The Japanese call it “Gariban” and the original Edison version was called “Mimeograph”. For a printmaking process, it really checks a lot of boxes for me as an artist. It is highly reliant on hand work, can reproduce fine linework, and requires no crazy solvents or chemicals or heavy machines.

Some months after the studio visit, Yukino and Yoshio invited me to make work for a group exhibition. Thinking back to our initial meeting, I wanted to use Gariban. However, my initial attempts were a bit of a disaster. The process was still too new to me. So I instead relied on another old handmade printing process — one far older than Edison’s Mimeograph.

Many of you will know that I have been working with Japanese style wood block printing for several years now, and yet am still getting comfortable enough to produce work with it.

There is good reason for that.

An Army of Artisans

In the old days of block printing in Japan, the artist was almost completely separate from the process of printing. They would make a painting and/or linework, with the intention of it becoming a wood block print, and that was often the end of it for them. The artist would hand their drawing to the head of a print studio, who then passed it to another artisan for translation into a printing design.

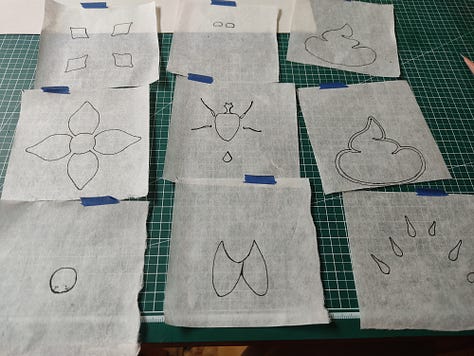

In shin-hanga, one artwork could require several — sometimes dozens — of final drawings. Why? Because each color in the final image needs its own carved woodblock. Each of these drawings then, was used as the template for carving and printing one of the colors in the artwork.

The final drawings were pasted directly onto wood blocks. Then, a master carver would take a blade to each block, carving directly through the drawing and into the wood — destroying the original in the process, but preserving it as a near-exact relief in the grain.

These numerous hand-carved blocks were then inked by the actual printmaker, whose job is was to print each color, one after the other onto the same paper with meticulous accuracy, so the colors and lines were perfectly aligned on the paper.

Interestingly, in Western block printing, oil based ink is typically rolled onto wood blocks, and to press that ink to the paper, a gigantic and very heavy press machine is often used.

Japanese block printing is quite different. There is no heavy machinery involved. Every part of the process is something that can be — and sometimes was — done in someone’s living room. The ink is also typically water-based. Transferring that ink from a block to the paper only requires your hand and a barren, rubbed vigorously but precisely with the paper aligned to the registration mark, notched into the corner of each block.

Carry out this process for each color, multiple times, accurately aligned, and you can produce amazingly vivid color reproductions, like the ones Katsushika Hokusai was famous for.

But the process typically requires an army of artisans to accomplish. Few still exist. Although in Tokyo, a Canadian printmaker named David Bull operates a traditional print shop, with many talented employees producing work with this method.

But I have no such army of artisans!

So I need to carry out each of the processes by myself. It takes time, but is actually really joyful, good meditation. It is also somewhat miraculous to see a design move from your sketches, to a piece of wood, and then to a final print run. All with your hands, in a tiny studio, without the use of a computer or even so much as electricity.

There is some radical kind of power in this act.

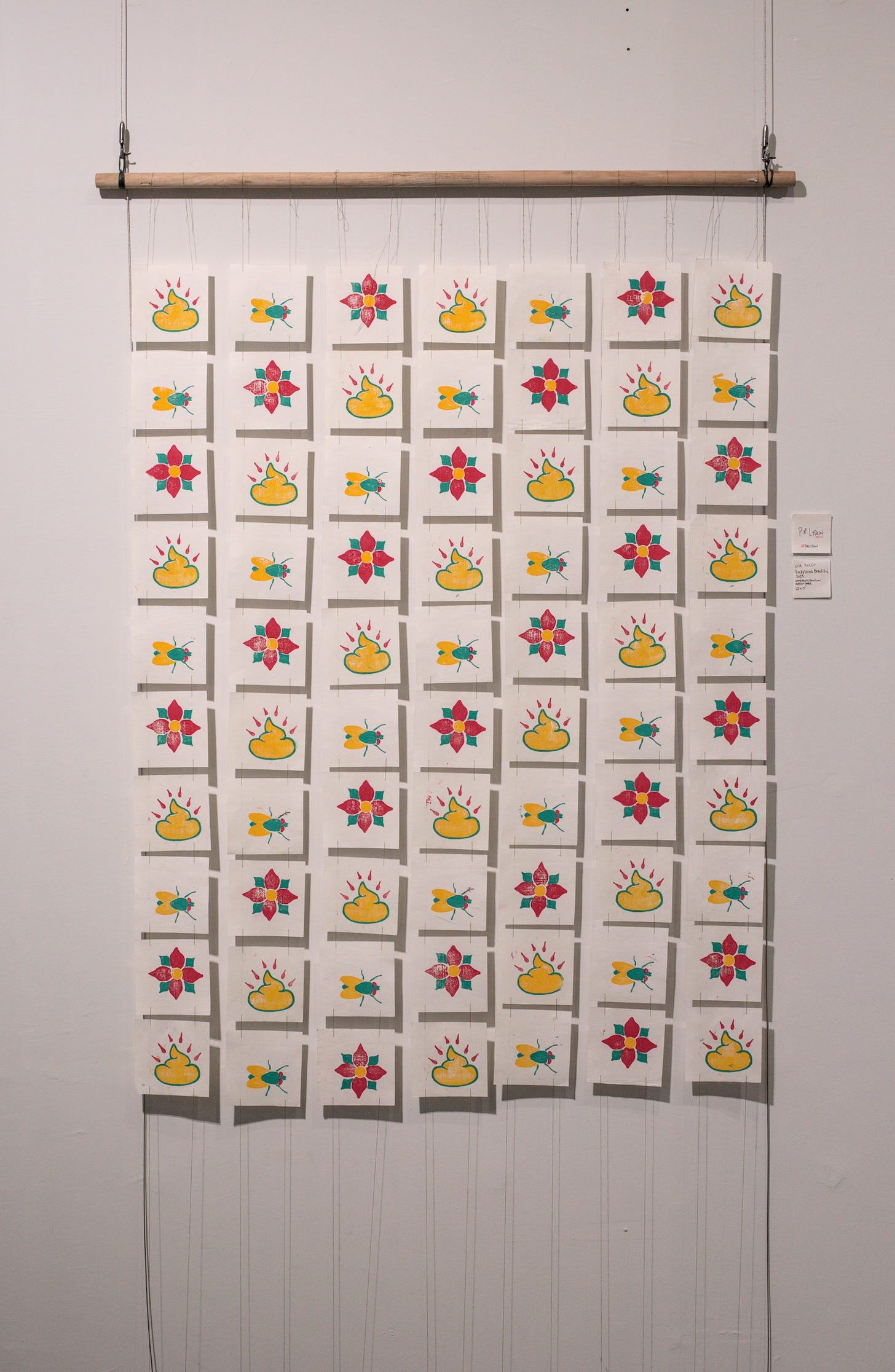

For the group exhibition in Japan then, my designs for the block prints are somewhat simple and small. There are three designs, each one with three colors. That is nine wood blocks in total. Inked, printed, and repeated to form a pattern reminiscent of the work that adorns the ceilings of Korean temples where Suhee and I live.

Well, to a point.

A Golden Poop

The colors and style of these designs are basically inspired by Korean temple motifs. In particular, one temple here in Tongyeong has a ceiling at the entrance gate adorned with a flower motif. That flower is the basis of the one you see in the artwork.

But what about the pile of golden poop and the fly?

Let’s be honest — there’s a lot of shit in our lives lately, isn’t there?

There always has been. But in the cycle of things, shit is important. Truly. Have you seen flowers in a garden lately? Or a lush wild forest? Or food on your table that relied on fertile soil?

In one way or another, they all tie back to shit.

We sometimes forget that, ecologically speaking, all of the beautiful things are born from decaying things. All of the food you eat is nourished by some kind of animal feces or carcass. Life comes from death. The shit in life, and the flies that flock to it, are prerequisites of what we call beauty.

In this, they are just as important as the flowers.

And so the million ugly things are born into the million beautiful things.

That is a law of nature, and there is no other way.

This artwork then, is a riff on the sacredness of everything, and the understanding that today’s muck is the compost for tomorrow’s flowers.

Golden poop. A sacred fly. A vibrant flower.

Beauty takes many forms.

When we must, we can wade through it all with appreciation.

Thanks to Yukino and Yoshio sensei for inviting me to exhibit in Senboku Art Now もぬける展, a small yet inspiring exhibition of art in Sakai, Japan.

—

Questions: What is your golden poop lately? Can you find a line between the unpleasant and the beautiful?

Next Week: It’s Father’s Day. There might be something here related to that.

Another Story: This story mentioned Hokusai. He was kind of an ecological urbanist buff. In his own way…

Hokusai, Oi, and the Ecological Mega-City

For development to be useful and sane, it must be tethered to the reality of our place in nature and the cosmos.

Thanks for letting me into your world. Feel free to chime in below, or to introduce yourself. You can help this project grow by thinking of someone else who might like this work, and clicking the magic button below.

Not yet signed up yet to get these stories to your inbox? No problem, you can do that below. You can also join our supremely awesome club of paid subscribers who get special perks from me (like handmade block prints).

What!? No one has answered what their golden poop is yet!!? lol.

I’ve been checking Substack all week looking for your post but it never popped up…till I checked email.

Thank you for this reminder that the lotus grows from the mud. My golden poop is the suffering I’ve endured all school year from my neglectful students. It’s revealed to me how to endure through long droughts of suffering and strengthened my self trust….which I suspect might come in handy in the future.

You might enjoy learning about the 20th-century Sōsaku-Hanga movement. Artists who were part of this movement did their own prints. I’m a particular fan of Umetaro Azechi.