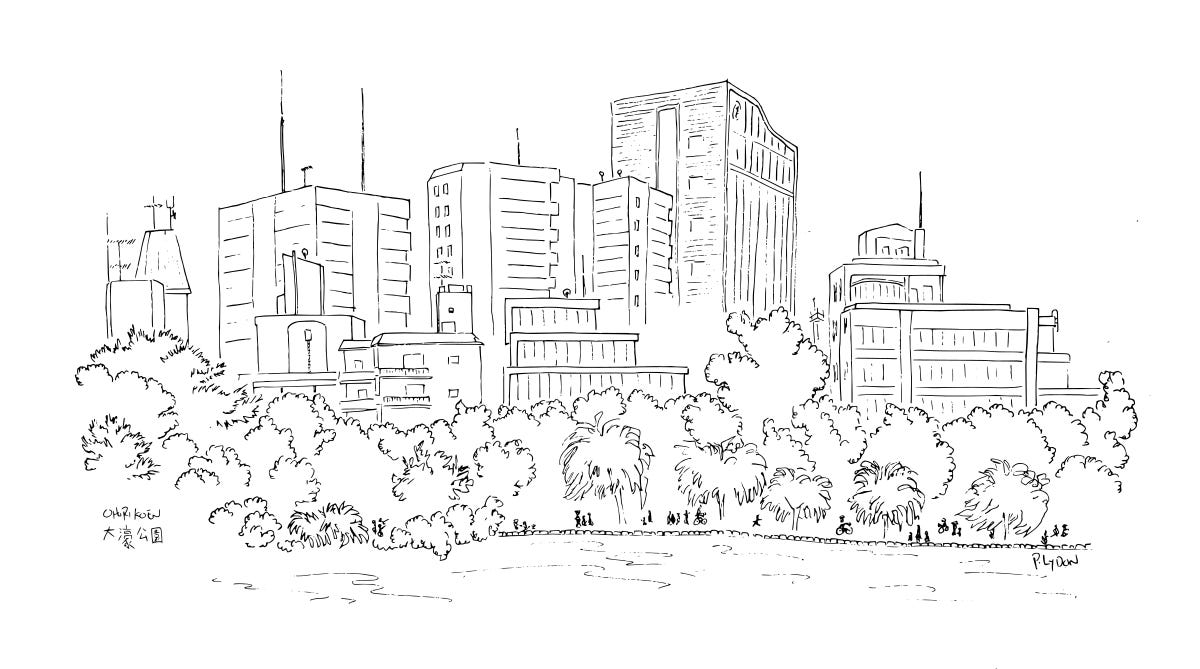

Our reasonable urbanism recipe book starts today, at Ōhori Park (大濠公園) in Fukuoka, Japan. This is the wide view, looking to the west, from the old castle, over the park grounds, and into Fukuoka, the city of 1.5 million inhabitants that encircles the park.

Once filled with turrets and keeps and wartime training grounds, Ōhori Park is now home to forests, gardens, and a large lake. The perimeter where sacred ground meets city remains roughly in the same place as it has for centuries. The big difference these days, is that everyone is free to cross the moat. Many do, for a jog, or on their way to school, or to take a nonfat sakura caramel frappuccino at a Starbucks located in the forest by the lake — a location with no drive through and no parking lot, yet which maintains a steady que out the door nonetheless.

Standing here atop the ruins of the castle, and rotating one’s sight-line in any direction, the details change. Tall buildings shift in form. Terraced apartments become wider here, impossibly narrow there. Private residences are triangular here, strangely bulbous there. Just below my gaze on one side a group of women walk their dogs in the meadow, on the other side a short boy in a red uniform doubles on a line drive to center field and cheers erupt. Through it all, the outfits of the joggers and baseball players and coffee drinkers and schoolkids trickle around, tiny specks of every color dotting the green and grey landscape.

I could sit here all day. I do sit here for half the day at least, to watch the seemingly infinite variations of life doing what life does, and of buildings standing guard, and of the sun and clouds, slowly shifting light and shadow through all of it.

Even if the variations are infinite however, we can also say in the same breath that the patterns stay the same. In every direction there is an order. Meadow to lake, lake to Willows, Willows to Pines and finally to the towering Camphors that define the edge between park and city. The gradual rise in height from one of these to the next is not perfectly uniform, but it is apparent, and not without intention.

Looking past the rows of Camphors, our view finally leaves the park and enters the city proper. For much of the peremeter, the border between here and there is not a fence but more of a zone, where buildings and trees and birds and people and dragonflies interact with one another.

Rather than being cut off from the park by a broad avenue, the first row of urbanity here interfaces directly with the park grounds. In many cases, buildings in the city are portals into the park grounds. Viewing this now from a perch in the lake, the two meld together in a way, so that we might ask, are the buildings growing from the trees, or the trees from the buildings?

We might know, from our own experience, that such a scene is rather rare in modern urbanism. At the same time, we will also likely know, when we do encounter such a place, that it is somehow enchanting. That enchantment is quite well appreciated here.

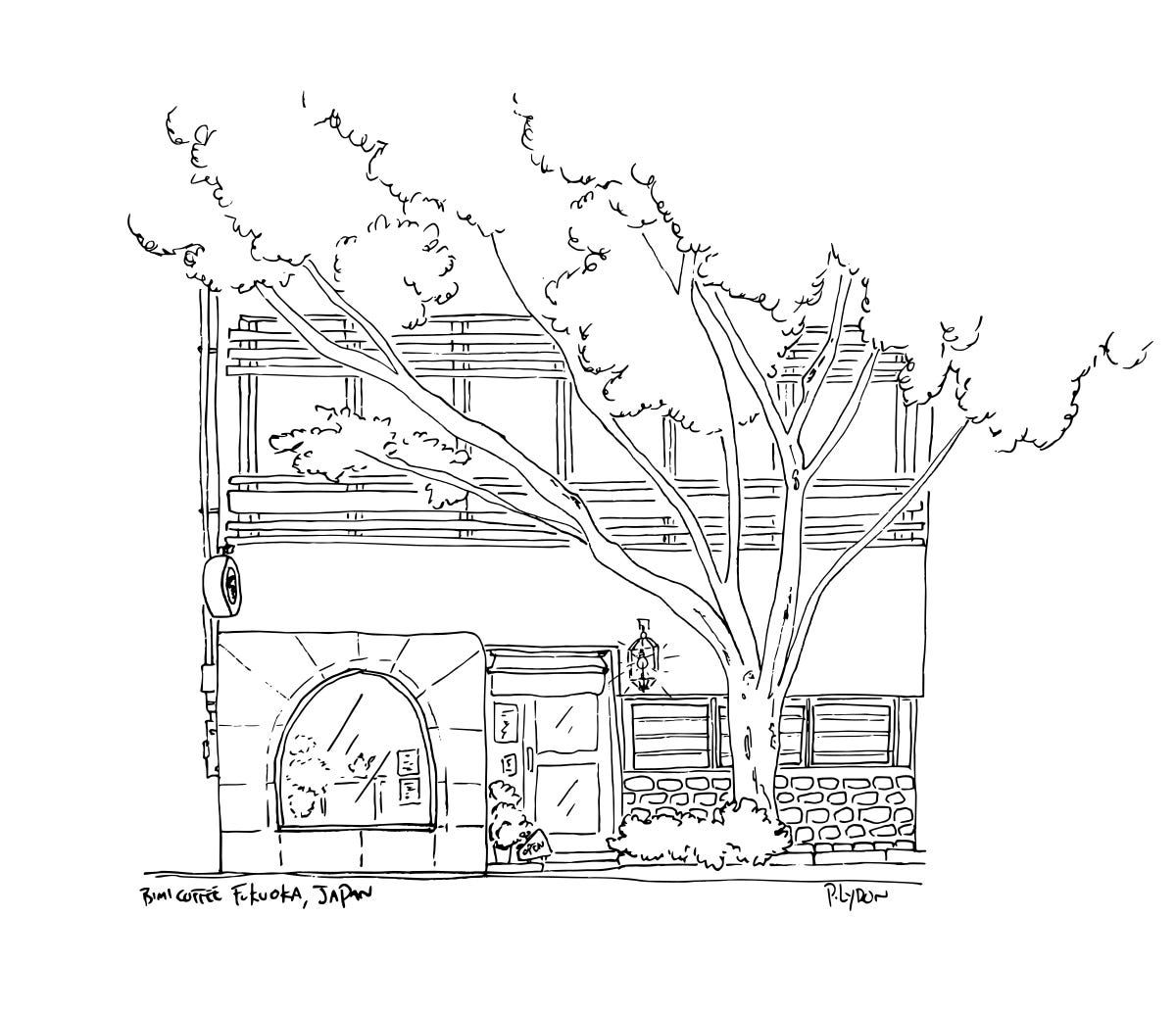

Walking along this city-park zone, I step inside a narrow building. Narrow as it is, the structure has two stories, built right up into the forest. Inside, among bins of coffee beans, a neatly dressed roasting master looks up and greets me. He directs me to the second floor, where half a dozen people sit with small cups of coffee, some in quiet conversation, some in contemplation at their coffee, or at the forest just outside the large wall of windows. Despite it being a particularly sweltering summer day, one of these large windows is open. This allows the smell of coffee to stir together with the medicinal woody tinge of the Camphor trees outside.

It is difficult to say how, but there is a certain comfort in being here. Something more than the combination of coffee and Camphor in the air. Can a forest embrace an entire room? If it can, that is something close to what it feels like in this moment.

I take a slow deep breath, and embrace it back.

From this zone at the edge of the park, the rise in height continues. Slightly taller apartments and production spaces further away from the park, then further away still are distinctly high-rise affairs. The latter punctuate the landscape, rather than dominate, at least from this view.

Then in the distance, on the other side of the district, the forest returns an echo. Earth’s own mountains rise in between the human-built ones, one way or another weaving their way through nearly every scene.

Later that night, walking along the edge of the mountain, the forest whispers something to me: the city is not forever.

As permanent as it may seem, and as old as the castle grounds are, something else holds sway here. This particular part of the city seems to recognize this truth. We are slowed down by the way these spaces are formed and by how they change in each moment. In this slowness we are reminded of that flow, of that cycle, that impermanance.

Perhaps more cities might venture to make such forms, such slowness, and such reminders more commonplace.

In reasonable urbanism, large parks and natural spaces are available, accessiable, and never cut off from their city but instead woven together, their edges becoming diverse zones of interspecies aliveness where city dwellers are embraced by the cycles of nature in their region.

Are there examples of this where you live? If so, it would be lovely to have you share them below, or send a note to me at thepossiblecity@substack.com

If you are new here, you might want to read the previous post in this series:

Reasonable Urbanism: A Ferry to Japan

Yesterday the winds were wailing, and the waves rolled me off my futon at least once during the night. Overall though, the experience was rather breathtaking in a good way. I had said I might need to visit Japan for this series. It is not so far, really. Yesterday I caught a train to Busan, and a few hours later, boarded the

Thanks for reading, for sharing this with others, for supporting as paid subscribers, and really in the end, just for being here to explore The Possible City with me.

See you next time.

It's lovely the images you have managed to glean from Fukuoka and Japan! I must admit that it made me a little jealous of the walkable nature of Fukuoka, coming from someone staying in the suburbs of Honshu. We still have our narrow sidewalks and sprawling suburbia!