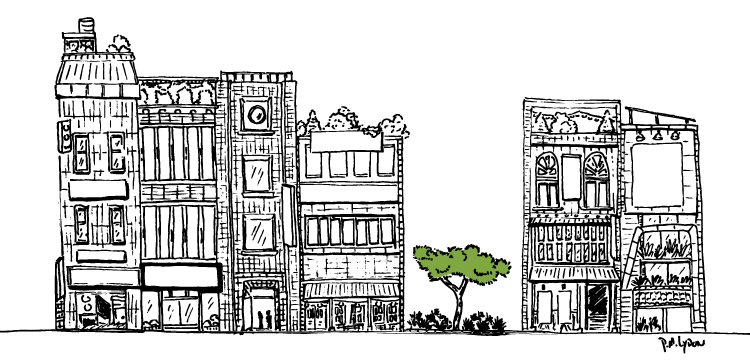

SHORT #2: Ode to Small Buildings

scale, ownership, and love in the equitable, regenerative neighborhood

In the old neighborhoods we have lived — in Osaka, in Takamatsu, in Daejeon — there are similar attributes to be noted. Blocks are packed with a dizzying array of houses and small businesses, stacked vertically and sandwiched horizontally, coming at you from different angles, and with different kinds of people from different walks of life, moving in out and about. All of this co-mingles together with public space and allotments for gardens, plants, and other living beings.

Here there are tiny restaurants tucked in every corner, owned by young people, by old ladies, or by chefs who immigrated from other countries. There are shops selling every imaginable style of clothing, and some unimaginable ones. Alongside these are small scale production workshops, the furniture makers, the breweries and makgeolli factories, the tailors for young and tailors for old, the galleries for high art and the galleries for street art. There are bars and clubs next to meditation and yoga studios — operating at different times of day of course — and then there are music lesson studios above jazz bars above basements where old men meet to play traditional music with each other.

I have just described some of the places for humans, but there are places for other living beings here, too. Weaving through all of this are thousand year-old zelkova and camphor trees connected to primeval forests where a dozen species of birds reside. Underneath these trees there are tiny pocket parks with pagodas where women meet to talk about gardening in the morning, and men take naps in the afternoon. Beside the trees are small meandering streams, stones covered in moss, schools of fish, watchful beady heron eyes, and sleeping mandarin ducks.

These are exciting, alive, socially and ecologically equitable places that exist in reality today. The likes of Jane Jacobs and Patrick Geddes might well adore them. Indeed, we would do well to design our cities with places like this in mind.

But this alone would not likely be enough.

You see, in walking past the zelkovas for a year, in tending to the tiny parks for five years, in riding a bicycle through the narrow streets for ten years, something becomes clear. The most well-loved cities in the world are not gifted to us by a master plan, but by the years that pass, and by the mindset and influence of the people and the nature who live there during those years.

But what goes into making a well-loved city possible in the first place? There are issues of social justice, the balance of economic and political power, geography and climate, building methods, codes, designs, policies, cultural practices, scale, and ownership.

Here, scale and ownership deserve careful attention. Done right, this duo are what enable — or prevent — residents to act on and change the city over time.

Knowing this, the way we approach scale and ownership today seems remarkably odd.

Single buildings take up entire blocks. Multiple blocks are owned by single developers. Neighborhoods that were once a cross-section of society, suffer a nearly complete loss of diversity in ownership, in who has access to space, and in how the city can be used.

A walk through the typical modern development here reveals no small-scale producers, no ten seat owner-operated sushi bars, and no old men hanging out and playing traditional music together. There are no women talking about farming because no one here is allowed to farm. There are no naturally meandering streams, no dozen species of birds, and certainly no primeval forests.

Similar development motives result in minor variations on the same themes all over the world, only with different shapes and paint colors.

Is there another scenario?

Bicycling back to our old neighborhood between the forest and the stream, our neighbor has just finished harvesting from his persimmon tree. As is the custom, I notice he leaves a few dozen fruits hanging up there for the birds. His wife hurries up to hand us a bag full of bright orange persimmons. In this simple interaction, I am assured that there is another way. This way asks that the nature of our built cities be re-aligned, not with our economic fantasies, but instead with our realistic needs. Needs like the health of people and the landscape. Needs like human creativity and community. Needs like a meaningful connection to the environments in which we dwell.

There are no hard rules to get there.

From a sampling of cities that are succeeding however, there do seem to be a few recurring themes. Alive, equitable, regenerative neighborhoods tend to have a good proportion of buildings that are:

Small enough to allow for a truly diverse city block

Economical enough to be financed by everyday people or cooperatives

Owned primarily by the folks who live or work in the neighborhood

That these three “themes” are followed, does not guarantee the transformation of neighborhoods. It also does not mean that these are the only themes, nor that if they were, that all buildings should always follow all of these themes. It also does not address the increasingly thick stacks of bureaucracy that stop this from happening in various places, and that must be either addressed, or ripped up.

It does overwhelmingly however, seem to give a good starting point for thinking about how socially and ecologically regenerative neighborhoods can arise … and hopefully, how we can cultivate more spaces for sharing persimmons, napping under camphor trees, and watching old men play music together.

Each week at The Possible City, I write and illustrate a short urban ecological adventure. Based on real people and places, these are stories of imaginative ideas and ways of thinking for equitable, resilient, regenerative cities. If you enjoyed this one, please subscribe and share it with others!

Have thoughts, ideas, or inspirations related to this article? Start or join the conversation thread at the end of each story, about what you think is possible and how we might get there, or send me a note.

Really loved the thoughts and the three themes you mentioned. I have no clue what can be done for implementation but someday really want to be a part of something like this. I have seen a lot of places destroyed in the name of development. But I hope to find good examples of good and conscious development.

My rationale brain likes the three aspects you laid out on what a sustainable hood entails. Feels achievable.